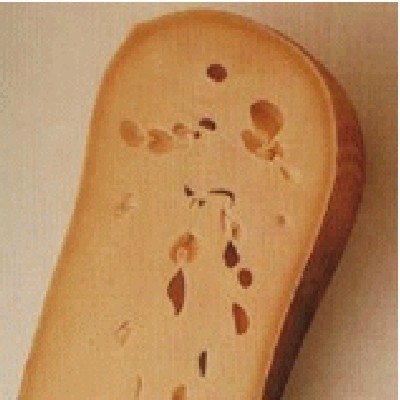

The riddle of representation:

two humans, a monkey, and a robot are looking at a piece of cheese; what is common to the representational processes in their visual systems?

Answer:

The cheese, of course. (1)

The Environment of Mind

Barry Smith

phismith@buffalo.edu

ROUGH DRAFT PREPARED FOR

THE CONSCIOUS MIND

CONFERENCE IN BUFFALO

NOVEMBER 5-6, 1999

Introduction

It is the mind-body axis

which occupies many of the papers in this conference. Here, in contrast,

and less Chalmingly, I shall concentrate on the orthogonal link between

mind or consciousness on the one hand, and its external environment on

the other. The two axes are of course related. There is indeed an analogue

of the mind-body problem (which concerns the relationship between our folk-psychological

ontology on the one hand and the physical ontology of the body) on the

side of the environment of mind. We might call it the mesoscopic-macroscopic

environment problem, and it concerns the relationship between our folk-physical

ontology of the medium-sized objects which surround us and the physical

ontology of the underlying microstuffs. More briefly: it is the problem

of understanding how common-sense realism and physical realism can be seen

to be compatible. My strategy in what follows will be, via a long detour

through Gestalt psychology and ecological psychology, to show what sort

of conception of world and environment is needed in order to make sense

of this compatibility.

Truthmakers

Consider the following judgment-pair,

which we are to understand as referring to one and the same event of tea-drinking

in Paris one summer's afternoon:

(A) 'Estelle is taking tea

with Chantal'

(B) 'Trotsky's great granddaughter is taking tea with Merleau-Ponty's niece'

The family of truthmakers for (B) is, intuitively, larger than the family of truthmakers for (A). (2) This is because Trotsky and Merleau-Ponty are involved in making (B) true in a way in which they are not involved in making (A) true. (B), we might say, demarcates, or captures within its representational scope, a larger portion of reality than does (A). The family of truthmakers for (B) extends back in time to comprehend objects which do not exist in the present.

Something similar holds now,

in relation to:

(C) 'Nicola is undergoing

a C*-neuron firing'

(D) 'Nicola is watching Prunella'

Here again, I want to argue,

the family of truthmakers for (D) is larger than the family of truthmakers

for (C). This is so, even if the event inside Nicola's head referred to

in (C) is identical to the event of watching Prunella referred to in (D).

(3) The families of truthmakers for these two judgments are different

in virtue of the different representational scopes of the two judgments,

which trawl through reality in different ways.

The Environment of Mind

I want to make sense of

this difference is in terms of different environments: the environment

that is picked out by (C) is a certain cortical region inside Nicola's

head; the environment picked out by (D) is a certain surrounding region

of external reality in which Prunella, too, is included. Students of the

mind-body problem from Descartes to Fodor have, notoriously, almost always

conceived the subject of mental experience in isolation from such surrounding

environments. One exception to this rule is the Gestalt psychologists (above

all Kurt Koffka and Kurt Lewin), who sought to understand the relations

between acts and objects as parts or moments of a larger relation of engagement

between subjects and objects in a common physical world. They embraced,

in other words, what one might call an ecological approach to psychological

phenomena. Koffka and Lewin in their turn influenced two American psychologists

J. J. Gibson and Roger Barker, both of whom (independently) conceived their

work under the banner of 'ecological psychology.' In what follows I shall

attempt, in the spirit of Gibson and Barker, to give an account of the

environment of mind in a way which will leave us in a position to understand

the way in which (C) and (D) have different representational scopes.

While the Gestalt psychologists were among the first to investigate the relations between mental experiences and associated processes in the brain, they still, when turning to the external environment of human behavior and perception, saw the latter as something like a manifest image constructed by the human subject. Hence they were left with the task - which we might think of as an externalized counterpart of the mind-body problem - of explaining the relation between this constructed environment and the world of physics.To see the nature of this problem, it will be useful to quote the passage from Koffka's Principles of Gestalt Psychology in which a fateful distinction between the psychological (or 'behavioral') and physical (or 'geographic') environments is introduced:On a winter evening amidst a driving snowstorm a man on horseback arrived at an inn, happy to have reached shelter after hours of riding over the wind-swept plain on which the blanket of snow had covered all paths and landmarks. The landlord who came to the door viewed the stranger with surprise and asked him whence he came. The man pointed in the direction straight away from the inn, whereupon the landlord, in a tone of awe and wonder, said: 'Do you know that you have ridden across the Lake of Constance?' At which the rider dropped stone dead at his feet.

The Problem of the 'Two

Worlds'

In what environment, Koffka

asks, did the behavior of the stranger take place? 'The Lake of Constance.

Certainly [... and it is] interesting for the geographer that this behaviour

took place in this particular locality. But not for the psychologist as

the student of behaviour.' The latter, Koffka insists, will have to say

that there is a second sense to the word 'environment,' according to which

'our horseman did not ride across the lake at all, but across an ordinary

snow-swept plain. His behaviour was a riding-over-a-plain, but not a riding-over-a-lake.'

(Koffka 1935, pp. 27f.)

How, then, are we to understand the relationship between the physical and the psychological environment? The tale of the ride across Lake Constance tells us that we cannot conceive these two environments as identical in every case. Three alternatives can now be distinguished:

(1) We can say that these two environments are always distinct (and thus embrace a 'two-world' hypothesis). We then gain the advantage of a uniform domain for psychological science, but we face the problem of explaining how this psychological domain (and our psychological life) might ever come into contact with the domain of physics.

(2) We can deny the usefulness of the concept of psychological environment, and insist that it is the geographic (physical, biological) environment that is relevant to the understanding of psychological phenomena in every case. Our mental life is then subject, on this account, to the possibility of a radical sort of ontological error.

The Gestaltists embraced

the first of these two alternatives. They were consequently not able to

come to a coherent account of the relationship between the psychological

environment (and psychologically experienced objects) and the transcendent

world of physical things. This is true even of the most sophisticated theories

of the psychological environment such as those advanced by Kurt Lewin and

by Meinong's student Fritz Heider: the psychological environment is for

them, too, something that is dependent upon the ego (something that is

present even in dreams: Heider 1959a). And it is true, also, of mainstream

psychology today, which characteristically adopts the standpoint of 'methodological

solipsism.' Thus Fodor (1980) argues that if a genuine ('nomological')

science of psychology is to be possible at all, then a hypothesis of representationalism

must be adopted according to which mental processes are to be understood

n terms of relations that organisms bear to immanent mental representations.

The issue of the relationship between psychological and physical phenomena

is hereby bracketed forever in order to ensure an ontologically uniform

domain for psychological science within which both true and false beliefs

and both veridical and non-veridical perceptual phenomena can enjoy equal

civil rights.

Ecological Realism

Ecological psychologists,

in contrast, embraced the second alternative. Thus Gibson and Barker see

normal psychological experience not in terms of a succession of relations

between acts on the one hand and objects in some special 'realm' on the

other, but rather in terms of a topological nesting, whereby the

sentient organism is housed or situated within a surrounding physical environment

of which it serves as interior boundary. (4)(1)

Its perceptions and actions are dependent features of this total subject-environment

relation, and are capable of being properly understood only as occurring

within the wider surrounding framework. At the same time the environment

is itself to be conceived as something that falls within the realm of physics.

In perception, as in action, from the Gibson-Barker point of view, we are embrangled with the very things themselves in the surrounding world, and not, for example, with 'sense data' or 'representations.' Perception is not a matter of the processing of sensations. Rather, it is part of that direct linkage between the perceiving organism and its environment which grows out of the fact that, in its active looking, touching, tasting, feeling, the organism as purposeful creature is bound up with those very objects - the ripened fruit, the crumpled shirt, the empty glass, the broken spear - which are relevant to its life and to its tasks of the moment.

Gibson and Barker thus embrace a radically externalistic view of mind and action. We have not a Cartesian mind or soul, with its interior theater of 'contents' or 'representations' or 'beliefs and desires' and the consequent problem of explaining how this mind or soul and its psychological environment can succeed, via intentionality, in grasping objects external to itself. Rather, we have a perceiving, acting organism, whose perceptions and actions are always already inextricably intertwined with the parts and moments, the things and surfaces, of its external environment.

For Gibson, reality as a whole is a complex hierarchy of internested levels of parts and sub-parts: molecules are nested within cells, cells are nested within leaves, leaves are nested within trees, trees are nested within forests, forests are nested within Special Federal Forest Protection Zones, and so on. (5) Each type of organism is then tuned in its perception and action to objects on a specific level within this complex hierarchy - to objects ('affordances') which are the environmental correlates of adapted traits on the side of the organism and which together form what Gibson calls the organism's 'ecological niche'. (6) A niche is that into which an animal fits (as a hand fits into a well-fitting glove). The niche is that in relation to which the animal is habituated in its behavior. (7) It embraces not only things of different sorts, but also shapes, textures, boundaries (surfaces, edges), all of which are organized in such a way as to enjoy affordance-character for the animal in question in the sense that they are relevant to its survival. The given features motivate the organism; they are such as to intrude upon its life, to stimulate the organism in a range of different ways.

The perceptions and actions of human beings are likewise tuned to the characteristic shapes and qualities and patterns of behavior of our own respective (mesoscopic) environments. This mutual embranglement is however in our case extended further via artefacts such as microscopes and telescopes, and via cultural phenomena such as languages and institutions of law and politics. To learn a language is in part to extend the range of objects in relation to which we are able spontaneously to adjust our behavior and thus it is to extend radically the types of niche or setting into which we can spontaneously fit. Philosophers, in contrast, even those philosophers with the ambition to come to grips with the realm of common-sense experience, have shown a tendency to adopt philosophies which reduce this realm - on the pattern of the doctrine of 'logical constructions' - to objects of a monistic flavor. The Wittgensteinian conception of the common-sense world in terms of 'language games' is an improvement on monistic theories. Unfortunately, however, it puts the cart before the horse. This is first of all because language, too, (if we are right) is a phenomenon which can be understood only within the framework of an ontological theory of environments - where language gets used such usage itself is under all normal circumstances embedded within environmental contexts of one or other familiar sort. But it is also, and more importantly, because to seek an account of our human common-sense reality in terms of language, as some Wittgensteinians have been wont to do, is to attempt to explain the whole in terms of one relatively late-developed part. Thus it is to place obstacles in the path of accounting for those many features of human behavior which are shared also by non-human animals.

Is Gibson a Realist?

A science of human environments will of course look very different

from any science of the more standard sort. The challenge, as Gibson saw,

is to develop a realist science of environmental settings which will be

'consistent with physics, mechanics, optics, acoustics, and chemistry'

by taking seriously the idea that ecological facts are 'facts of higher

order that have never been made explicit by these sciences and have gone

unrecognized.' (Gibson 1979, p. 17) He uses the term 'ecology' precisely

in order to designate the discipline that should encompass these higher-order

facts; it is 'a blend of physics, geology, biology, archeology, and anthropology,

but with an attempt at unification' on the basis of the question: what

can stimulate the organism? (Gibson 1966, p. 21)

Gibson thus stands out from the bulk of contemporary psychologists in rejecting all varieties of representationalism in favor of a position he calls 'direct realism' according to which (once again:) we are, as a result of adaptation, bound up directly and spontaneously in our normal psychological experience with the objects themselves in the physical world. We ourselves form part of the physical environment.

There is a puzzle, however. For Gibson's ecological perspective is in other respects very close to representationalist and constructionist theories of a distinctly idealist stripe. In an important paper entitled "Is Gibson a Relativist?" Stuart Katz helps us to understand how this apparent conflict could have arisen by drawing attention to passages in Gibson's work which seem to negate the standard realist interpretation of his views and thus draw him closer to the phenomenologists. Katz points in particular to the following characteristic statements from Gibson'sEcological Approach to Visual Perception: animal-and-environment make an inseparable pair. Each term implies the other. No animal could exist without an environment surrounding it. Equally, although not so obvious, an environment implies an animal (or at least an organism) to be surrounded. (1979, p. 8) The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what itprovides or furnishes,whether for good or ill. - I mean by [affordance] something that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment: an affordance is neither an objective property nor a subjective property; or it is both if you like. An affordance cuts across the dichotomy of subjective-objective. - It is both physical and psychical, yet neither (1979, p. 129). These passages dictate, according to Katz, a reading of Gibson according to which (as according to Uexküll) different species live in different worlds. Water is for you and me a substance; for fish it is a medium which substances inhabit. Hence the question arises: Do terrestrial animals perceive water correctly and aquatic species incorrectly, or vice versa? Gibson as relativist tells us no. Each lives in a different world and, complementarily, each perceives differently. Water is a substance in one world and a medium in another; it is not absolutely substance, nor is it absolutely medium. 'The animal and its environment, remember, are reciprocal terms.' One could never say what water is, without saying for whom it is, and conversely. (Katz 1987, p. 120)

Reasons for Representationalism

But Katz's argument is flawed, and in coming to understand why this

is so, we will discover which modifications of standard methodologically

solipsist and representationalist views must be made if we are to bring

them into harmony with ecological realism.

Note, first of all, that there are two principal motivations for representationalist views of perception: (1) the problem oferror, and (2) the problem of seeming global incompatibilities between different systems of representations.

The existence of perceptual error, according to familiar arguments (involving bent sticks and the like), reveals that perception itself cannot be solely a product of sensory inputs. It tells us that, on occasion at least, for example in cases of hallucination, perceptual objects are in some sense created or constituted by or with the help of the perceiver. A perceptual representationalist is one who holds that the objects that are given in perception are always constructed or constituted in this sense (hence they belong to a special world, a world of representations). The representationalist is thus able to do justice to the fact of perceptual error without abandoning the goal of a unified theory of perception - but only at the price of cutting off his theory from any roots in the real world of mind-independent objects. The realist solution to the problem of error, on the other hand, denies that what is phenomenologically experienced as the unitary phenomenon of perception is in fact a unitary matter at all. Rather, we must distinguish two types of perceptual setup, and correspondingly two distinct tasks for the theory of perception. On the one hand is the task of providing a theory of perception in the strict sense - a theory of successful, veridical, world-embrangled perception of the normal sort. On the other hand is the quite different task of giving an account of perceptual error (of the different types of shortfall from this standard, veridical case).

The second motivation for representationalism might be formulated as follows: our common-sense perceptual space has a Euclidean structure (or a structure closely related thereto); the space of the physicist has another, quite different structure; and it may well be that the perceptual spaces of mice, of spiders, of clams, have other structures again. Not all of these structures can be true of space as it is in itself. Hence, the argument proceeds, our (and the mouse's, and the spider's) perceptual spaces are mere 'representations'. And what goes for space holds for other features of the manifold environments of perception, too, so that, again, it is as if each species lives in its own special world.

It is a constructivist, relativist, projectivist, Kantianist conclusion

of this sort which Katz attributes to Gibson. But, to remain with Katz's

own preferred example, space (as we may here assume) is a continuum. Like

all continua it can be partitioned in a range of mutually incompatible

ways (as a cheese can be sliced in such a way as to produce either triangular

or rectangular or disk-shaped segments but not all of these at once). All

members of a family of mutually conflicting 'perceptual spaces', now, may

very well turn out to be compatible after all, if they can be interpreted

as expressing distinct partitions, for example partitions on different

levels of granularity, of one and the same reality. In this way the second

motive for representationalism may be resisted, too, and with it also the

argument put forward by Katz for a representationalist reading of Gibson.

The Big Cheese

The world of environments, for Barker as for Gibson, is a complex hierarchy

of internested levels of parts and sub-parts. But neither Barker nor Gibson

has at his disposal a theory of partsor

components and of

the wholes into which they are nested; neither has, in other words, a

mereology,

(8)

in terms of which it would be possible to formulate an overarching account

of the ways parts can fit together within their respective environments

and of how environments themselves can fit together in a larger, hierarchically

organized order. It is for this reason, I want to argue, that the ecological

approach appears to fall victim to the argument of Katz.

With the resources of a general mereology, however, we are in a position to comprehend within a single theoretical framework what is involved when one and the same reality is partitioned in distinct, cross-cutting ways by organisms or cognitive subjects approaching this reality each from its own particular perspective.

Mereology allows us to do justice to the ways in which, in the realm of environmental settings, entities of radically different sorts are able to become unified together into wholes: the unity in question is at least in part a unity of psychological demarcation (it is analogous, as we suggested above, to the unity involved in the geopolitical realm, where even spatially widely scattered entities such as Indonesia or the United States are able to enjoy the status of unitary wholes even in the absence of any physical unification of their parts).

Mereology allows us finally to understand, in full conformity with the

realist perspective, how different languages, different theories, and different

systems of animal behavior and perception are able to generate their own

precisely fitting partitions of one single reality. The various animal

behavior-systems generate partitions of reality into ecological niches.

Human perception and action together generate that mesoscopic partition

of reality we call the common-sense world. And other sorts of partitioning

of reality are generated, for example, by the acts of physicists, paleontologists,

historians, and even mathematicians. (The mathematician, we might say,

is tuned to those subtle parts of reality which are its mathematical forms

or structures.) Each such group of disciplinary specialists lives in its

own precisely tailored disciplinary world, its precisely fitting surrounding

environment, exactly in the way described by Husserl in Ideas II.

(9) Now, however, we can understand how this multiplication of

environments can be fully compatible with the realist perspective and with

the hypothesis of a single, common world. The ultimate ontology will be

scientific, but it will have room not only for physics but also for mesoscopic

structures built up on the basis of physics, especially structures of the

type to which everyday human behavior and perception are tuned.

References

Armstrong, David M. 1997 A World of States of Affairs, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barker, Roger G. 1968 Ecological Psychology. Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Barker, Roger G. and Associates 1978 Habitats, Environments, and Human Behavior. Studies in Ecological Psychology and Eco-Behavioral Science from the Midwest Psychological Field Station, 1947-1972, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Fodor, Jerry 1980 "Methodological Solipsism Considered as a Research Strategy in Cognitive Psychology," Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3, 63-73. Reprinted in Hubert L. Dreyfus, ed., Husserl, Intentionality and Cognitive Science,Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982, 277-303.

Fox, John F. 1986 "Truthmaker", Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 65, 188-207.

Gibson, J. J. 1966 The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems, London: George Allen and Unwin.

Gibson, J. J. 1979 The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, repr. 1986, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Heider, Fritz 1959 On Perception and Event Structure, and the Psychological Environment, Selected Papers (Psychological Issues, Vol. 1, No. 3), New York: International Universities Press.

Heider 1959a "The Description of the Psychological Environment in the Work of Marcel Proust," in Heider, 1959, 85-107.

Heider, Fritz 1959b "Thing and Medium," in Heider 1959, 1-35.

Husserl, Edmund 1952 Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie. Zweites Buch: Phänomenologische Untersuchungen zur Konstitution, M. Biemel, ed. (Hua IV), Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy. Second Book: Studies in the Phenomenology of Constitution, translated by R. Rojcewicz and A. Schuwer, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1989.

Katz, Stuart 1987 "Is Gibson a Relativist?", in A. Costall and A. Still, Cognitive Psychology in Question, Brighton: Harvester, 115-127.

Koffka, Kurt 1935 Principles of Gestalt Psychology, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Mulligan, Kevin, Simons, Peter M. and Smith, Barry 1984 "Truth-Makers",Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 44, 287-321.

Schoggen, P. 1989 Behavior Settings. A Revision and Extension of Roger G. Barker'sEcological Psychology,Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Smith, Barry 1995 "Common Sense," in Smith, Barry and Smith, David Woodruff, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Husserl, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 394-436.

Smith, Barry 1996 "Mereotopology: A Theory of Parts and Boundaries", Data and Knowledge Engineering, 20, 287-303.

Smith, Barry 1999 "Truth and the Visual Field", in Naturalizing Phenomenology. Issues in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science, edited by J. Petitot, F. J. Varela, B. Pachoud, J.-M. Roy, Stanford: Stanford University Press, forthcoming.

Smith, Barry 1999 "Truthmaker Realism," Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 77 (3), 1999, 274-291.

Smith, Barry and Varzi, Achille 1999 "The Niche", Noûs, 33: 2, forthcoming.

Smith, Barry and Varzi, Achille C. 1999 "The Niche", Noûs,

33:2, 198-222.

Endnotes

1. With thanks to Shimon Edelman. See http://www.ai.mit.edu/~edelman/archive.html

2. I draw here on truthmaker approaches to the correspondence theory of truth such as have been defended by Armstrong, Fox, and Mulligan, et al.

3. One difference between the two events might be this: the former is independent of Prunella, the latter not; compare the relation between a man and a husband.

4. On the formal ontology of this organism-environment relation, and on its Aristotelian roots, see Smith and Varzi 1999.

6. Gibson's own account of this relationship of tuning - in terms of information pick-up - need not detain us here. We are concerned, rather, with the ontological underpinnings of the ecological theories of Gibson and Barker, a detailed formal treatment of which is to be found in Smith and Varzi 1999.

8. See Smith 1996, 1999; Smith and Varzi 1999.

9. Husserl's position in Ideas II is exactly the position attributed by Katz to Gibson (with all the concomitant metaphysical confusions; see my 1995).